Inner workings of malware vaccines

Malware vaccines apply harmless parts of malware to a system to trick malware into malfunction. It is not a coincidence that the security industry adopted the term vaccine from medicine because there is a resemblence to medical vaccines which apply inactive or weakened parts of viruses to a person in oder to protect. But the analogy stops there. Malware vaccines do not improve the security reponse of the system.

The harmless malware parts that vaccines apply are often so called infection markers. Malware usually tries not to infect a system twice because this has unintended consequences. For that reason malware may place infection markers after a successful infection. If the malware finds such a marker, it will refrain from installing itself again. A vaccine just places those infection markers without the malware, thus tricking the malware into thinking it already infected the system (cf. p. 2 [wich12]).

Vaccines can use other things than infection markers, e.g., they may cause an error in the malware by providing invalid data. Some malware writes data into the registry or into files like encryption keys, configuration settings, C2C servers. A vaccine may place invalid data that causes the malware to crash, malfunction or simply not working as intended by the author. A simple example would be the application of a non-existing C2C server for remotely controlled malware. One well-described vaccine that crashed previous versions of Emotet with a buffer overflow is called EmoCrash [quinn20].

In case of the STOP/DJVU ransomware vaccine, the ransomware is tricked into not encrypting files anymore. Without file encryption there is no leverage to demand a ransom, thus, the main malicious behavior is disabled by the vaccine.

Another, albeit different case, is the Logout4Shell vaccine by Cybereason. This vaccine is a benign malware akin toWelchia worm. Benign malware has malware characteristics like worm-propagation or virus replication, or exploitation, but the payload is meant to fix a problem. Welchia worm got famous for using the same propagation mechanisms like Blaster worm to clean Blaster infections as well as patching vulnerable systems. Logout4Shell is similar to Welchia because it actively exploits the Log4Shell vulnerability in order to fix the security hole. The exploitation itself is problematic because the changes can be applied without consent of the system's owner. Cybereason states in a Bleepingcomputer article that the benefits outweigh the ethical concerns considering the severety of Log4Shell exploit.

Advantages of vaccines over detection mechanisms

Vaccines have some unique advantages. They are passive, thus, unlike antivirus scanning they have no performance overhead for the system. Depending on the malware they may also work on already infected systems by shutting down the malicious behavior of the dormant infection (p.3 [wich12]). Vaccines also work independently from obfuscation, packing, polymorphism, metamorphism or similar evasion techniques.

In a study from 2012 at least 59.4% of the malware samples used infection markers (p.4 [wich12]). This study is obviously outdated, but the only one I could find about infection marker prevalence. I do believe that the magnitude did not change and vaccines could be developed for a substantial amount of malware families.

Malware vaccines are actively developed by some security companies, e.g., Minerva, however, compared to other malware protection mechanism like signature based detection vaccinations seem rather unpopular. Why?

To understand this let's take a look at a specific vaccine first: The STOP/DJVU ransomware vaccine.

STOP/DJVU ransomware vaccine

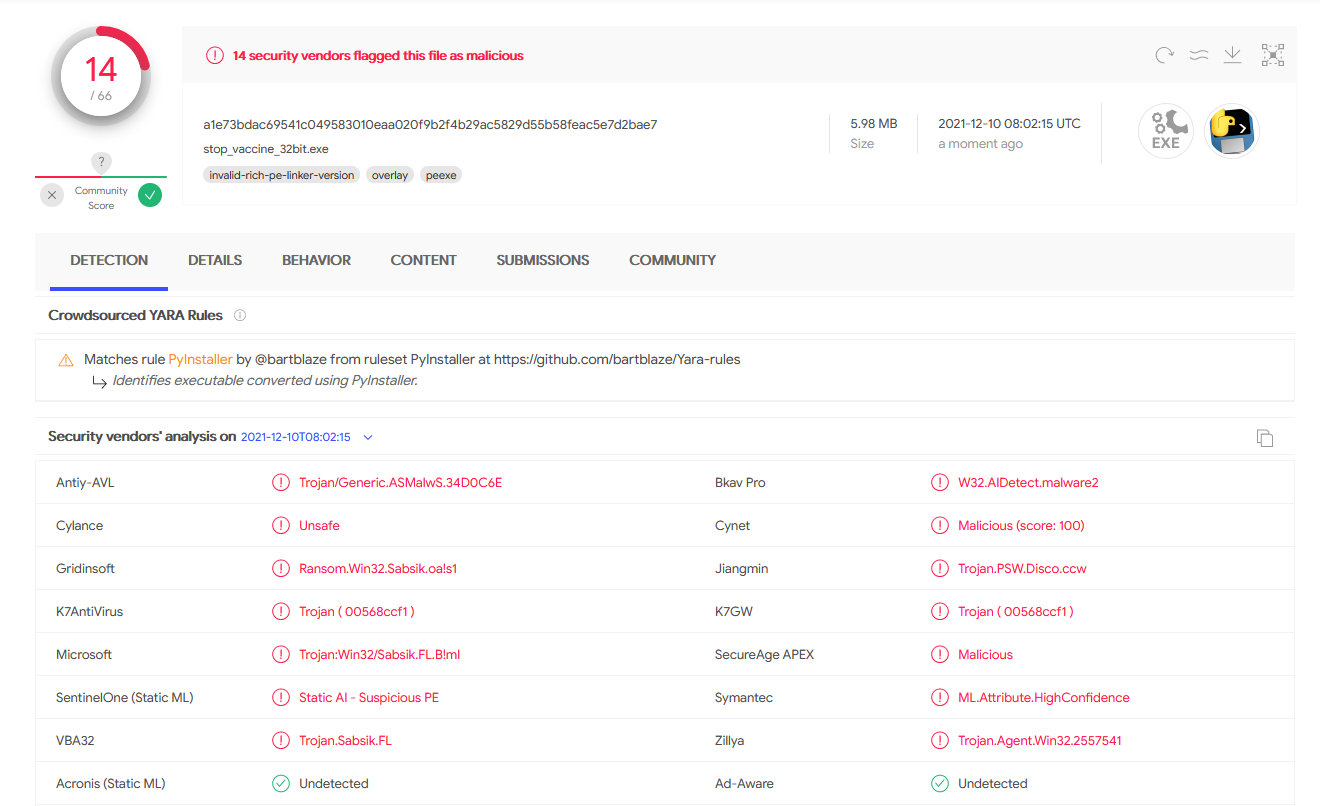

STOP/DJVU ransomware vaccine was created by John Parol and me. We published a tool on Github so that everyone can inspect and use it. Soon after publishing it, the tool got many false positive detections by antivirus vendors.

Additionally we added a section to our tool's readme to explain that systems are not entirely protected from STOP/DJVU ransomware after using this vaccine. The ransomware will still do things to the system that are not tied to encryption.

- in some cases the ransomware may still create ransom notes

- if files are smaller than 6 bytes, the ransomware will still rename them, but not change their contents

- this ransomware is often not alone but ships with additional malware like Vidar stealer, so disinfection of the affected system is still necessary despite the vaccine

So the only thing that the vaccine prevents is the encryption and (for most files) renaming. It is not sure that the vaccine stays on the system because security products will likely remove it. STOP/DJVU ransomware itself may also get an update at some point so that the vaccine does not work anymore.

Vaccines are no silver bullet

The main problem of vaccines is that they make a system look infected to other security products. Many of the more tech-savvy users use malware scanners additionally to their main antivirus product and these scanners detect infection markers as a sign of a prevalent infection. Not only do they remove these infection markers, they will find them repeatedly when the antivirus product re-applies them. That turns using the products alongside each other into an unpleasant experience for the user, who may come to believe that their main antivirus does not work against this threat, and that their system is never properly cleaned.

Forcing malware scanners to not detect such infection markers is a bad idea because this would eventually weaken their detection against real threats. These markers are actual infection signs and should continue to be detected as such. Hoping and preaching that users only use one security suite from one vendor is also not realistic. We have to live with cross-usage of other scanners.

Additionally vaccine protection is oftentimes silent, which means users will never know that there was an infection attempt. This is not desireable because users need to know that, e.g., the program they downloaded was a bad idea.

Malware vaccines may stay a niche defense mechanism for the everyday malware, but they are specifically useful to combat pandemic outbreaks. In that regard they are not different to medical vaccines.

References

[quinn20] James Quinn, August 2020, "EmoCrash: Exploiting a Vulnerability in Emotet Malware for Defense", www.binarydefense.com/emocrash-exploiting-a-vulnerability-in-emotet-malware-for-defense/

[wich12] A. Wichmann and E. Gerhards-Padilla, "Using Infection Markers as a Vaccine against Malware Attacks," 2012 IEEE International Conference on Green Computing and Communications, 2012, pp. 737-742, doi: 10.1109/GreenCom.2012.121.